At 8:15 AM, on August 6th, 1945, the United States dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan. Shortly after, on August 9th, 1945, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan. In the days and months following these historic events, several American and Japanese photographers documented the damage. However, only a select number of photographs were released to the public as film and photographic evidence of what occurred were confiscated and censored by the U.S. military.1 This paper will analyze, the various types of photographs that were gradually released to the U.S. news media from primarily 1945 until 1952. I will argue that during and after wartime, an uncensored and free press is essential for a viewing audience to adequately be informed of what occurred at the time. Censorship of photographs that showed the human effects of a nuclear bomb explosion consequently obstructed American citizens' abilities to more vividly use their imaginations and place themselves at the locations of where victims of the blasts once stood.

After WWII ended, people around the world indeed knew that in August of 1945 atomic bombs had devastated two Japanese cities. This paper will not examine whether or not the use of the atomic bombs was necessary or a morally justifiable act. Instead, the purpose of this paper will focus on how different photographs emotionally effected Americans. Along with various other media types, between 1945 and 1952, four issues of Life magazine were published containing photographs that showed the after effects of the atomic bombs. The photographs therein provide an excellent example of how Americans perceived the past event and how any similar historically significant events in the years and decades that followed could be perceived.

If the American public had been able to view more detailed photographs taken showing the aftermath of the atomic blasts, it is possible that stereotypical and racists views some had towards the Japanese could have been more hastily changed. The long-lasting censorship and regulation of photographs, whether shown or not shown to the public, unnecessarily delayed the surviving victims the necessary aid they required. The censorship also prevented people from becoming further educated about the bombastic power the atomic bomb had on people and not buildings when one is exploded over a metropolitan population. The unfortunate result of the censorship has resulted in a public who is either unconcerned and/or unaware of the true realities and degree of incredible human suffering that occurs during wartime.

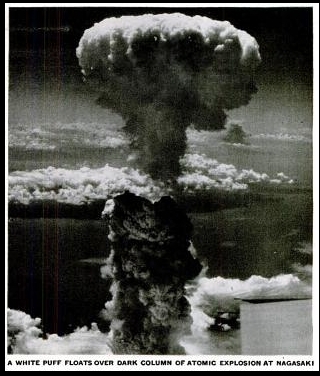

The first photographs showing the destructive power of the atomic bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were shown to the public in the August 20th, 1945, issue of Life. Two photographs provided by the United States Army Air Force each displayed a gigantic mushroom cloud hovering over the now demolished cities.2 Consequently, Americans who viewed the photographs could celebrate that American military and scientific progress brought an end to WWII and the possibility that possibly hundreds of thousands of American soldiers could be lost if an invasion of Japanese mainland was necessary.3

On September 17th, 1945, despite detailed photo-journalists' reports being available for publication, the photographs published in Life showed many for the first time the devastation the atomic bombs had on the ground. However, the issue did not show any photographs of those either killed or wounded. Instead, the issue published seven different photographs of destroyed infrastructure as well as one photograph (taken from a different vantage point compared to the photograph published a month earlier) taken seconds after detonation showing the atomic-mushroom cloud towering ominously over Nagasaki (fig. 1).

Fig: 1: The iconic mushroom cloud photograph hovering over Nagasaki.

What the articles in Life did not display were photographs showing the effects the atomic bombs had on people who perished or survived underneath the mushroom cloud. For example, the article, ”What Ended the War: The atomic bomb, according to Jap premier, threatened the extinction of the Japanese people,” stated that Japanese doctors reported “those who suffered only small burns found their appetite failing, their hair falling out, (and) their gums bleeding. They developed temperatures of 104 degrees, vomited blood, and died.”4 Despite the Japanese doctor's graphic and realistic account describing the trauma the bombs on had people, no photographs were shown which would allow readers to more vividly imagine the true power and devastation that resulted from the bombs being unleashed on the largely civilian population.

In the days and months after WWII concluded, photographers dispatched to Hiroshima and Nagasaki witnessed firsthand the effect the bombs had on humans within the blast radius. One of the first to arrive on the scene, in September of 1945, was United States Marine Corps photojournalist Joe O'Donnell. His assignment was to provide his superior officers with top-secret documentary photographs showing the devastation produced by the atomic bombs. The photographs he took were strikingly familiar to those displayed in the September 17th, 1945, issue of Life.

While assigned to take photographs for military and scientific purposes, O'Donnell was emotionally shocked by what he saw and in turn disobeyed his direct orders by taking and keeping personal photographs of what he witnessed. In 1995, O'Donnell's personal photographs were finally published by a Japanese publisher for distribution throughout Japan. Then, in 2005, Vanderbilt University Press published Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine's Photographs from Ground Zero which contained seventy-four of his impressive photographs.5

In 2011, O'Donnell's photographs were put on display at the Tennessee State Museum in Nashville, TN. An in-depth photo analysis on one of O'Donnell's landscape photographs provides a glimpse into what was going through his mind when he witnessed and photographed the remains of Hiroshima (fig. 2).

Fig. 2: A lone individual walks through the ruins of Hiroshima.

From the vantage point of where O'Donnell took the photograph, the remains of three destroyed (yet still standing) buildings appear in the upper-left, upper-right, and center of the photograph. From the upper-left to the bottom-right side of the photograph, a dusty gravel road is also easy to recognize. What stands out most in the photograph is the one person walking alone down the dusty road. From the caption that accompanied the photograph, the viewer is informed by O'Donnell that “One lone person walks near the ruins of Nagare-kawa Church 450 meters from Ground Zero. This is one of several low-altitude aerial photographs I took showing the complete destruction of the city.”6 The photograph, like those displayed earlier in Life, indeed allows viewers to emotionally distance themselves from the human suffering that occurred at ground level. Therefore, it would be relatively simple for anyone who viewed the photograph to draw the conclusion that the loss of life was minimal as no corpses or wounded people were show in the photograph.

However, the lone individual in the road is significant because it allows the viewer to place themselves walking amidst the rubble. Rather than only destroyed buildings being photographed, O'Donnell (as indicated in the caption) purposely included the individual in the road to add a glimpse into the possible loneliness survivors felt in the aftermath of the bombing. The presence of just one person in the photograph creates more of an emotional reaction in viewers compared to photographs containing no citizenry.

Landscape photographs, such as that shown in the O'Donnell photograph, was all the American public was exposed to in the first year after the atomic bombs were dropped. Historians Laura Hein and Marc Selden state in their article “Fifty Years after the Bomb: Commemoration, Censorship and Conflict,” limited, vague, and dull landscape photographs were shown to the American public to purposely give them the impression that the bombings provided a “depersonalizing (of) the victims…as bomb 'etiquette' (at the time) suppressed the emotional distance that many Americans have traveled since August 1945.” Hein and Selden also state that the landscape and mushroom cloud photographs produced a nice simple story presenting Americans as a brave, selfless, and united people.7 After the glorious victory over Japan, the general tendency and narrative that media outlets subscribed to indeed contained an unspoken “etiquette” that photographs showing human suffering caused by the atomic bombs should not be published. Effectively, not showing such photographs prevented rain from falling on any parades celebrating patriotic American victory.

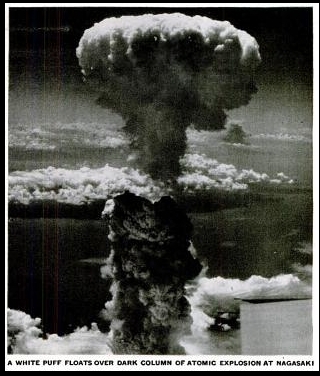

On June 30th, 1946, close to the one-year anniversary of when the atomic bombs were dropped, a report published by The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (USSBS) titled “The Effects of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki” was released to the public. While thousands of different photographs were taken showing the structural and physical results of the blasts, the USSBS report included only thirty-three photographs with thirty-one again showing nothing but ground and aerial views of structural damage similar to any city reduced to rubble during WWII. The human effects the bomb had on civilians underneath the mushroom cloud were shown in only two photographs that were taken on October 2nd, 1945, by an unknown Japanese photographer. The two photographs presented (from left to right) show a close-up facial view of a Japanese man wearing and then not wearing a baseball hat (fig 3).

Fig. 3: As stated in the USSBS, a hat provided sufficient protection for this individual to prevent serious injury.

The man was posed

for the photograph with his head orientated to his right to showcase

the radiation scars on the left side of his face and neck. The

caption states that the man was safe from suffering any severe damage

because "his cap was sufficient to protect the top of his head

against flash burns."8

The two photographs displayed in the USSBS report do not successfully

portray the true extent of human suffering that occurred underneath

the mushroom cloud.

From May 20th, 2011, until August 28th, 2011, a large collection of hundreds of USSBS' photographs were put on display at the International Center of Photography. The exhibition showed the destruction the atomic bombs caused from zero to seven-thousand feet outside the epicenter of where the bomb detonated over Hiroshima. The photographs displayed at the exhibit were also published in the book Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945. The editors of the book state that the collection of photographs “focused on the structural damage, bereft of human presence.” Furthermore, they state that the complete lack of a human presence in any of the photographs served an important purpose as American architects and engineers were now easier able to protect cities (but not necessarily citizens) from a future nuclear attack.9

The photographs displayed at the exhibit and in the book generally prohibited a great deal of the audience from having any shocking emotional responses sixty-six years after the bombings. The collection of landscape photographs inhibited the American public from having meaningful photographic evidence that would cause concern if nuclear weapons were ever to be used again. Truly, with so many people easily able to survive an atomic attack, where would the plethora of survivors reside if all the houses and other buildings that once stood suffered such a saddening, horrific, and untimely demise? Of course, it is simple nowadays to use sarcasm in regards to the insurmountable amount of dull landscape photographs the government released to the public. But, at the time, it would be hard to believe that people's imaginations contained any realistic mental imagery showing the human effects a detonated nuclear weapon would have on themselves if they were unfortunate enough to be in such a scenario.

Days after the

release of the USSBS report, as the Cold War anxiety began to spread

throughout the nation, a Universal newsreel made in cooperation with

the Army and Navy began to air nationwide on August 5th,

1946. The footage of the newsreel contained confiscated photographs

taken by Japanese photographers shortly after the atomic bombs were

dropped. The photographs in the film again gave little (if any)

indication that the Japanese people suffered at all from the nuclear

blasts. The film was largely used for propaganda purposes as it

showed medical wounds on people that have healed after just one year.

Evidence of the propaganda intention of the newsreel began at the

seven-minute mark when a dramatic under-water atomic bomb test is

shown with vacated military ships positioned for destruction. The

narrator on the film informs that the ships destroyed by the blast

went down in the cause of science and that if man can control the

atom he must also control himself from using atomic bombs because

"distance from the epicenter is the only defense one can have from

an atomic blast.”10

The newsreel, like photographs shown earlier in Life, avoided showing any human suffering that may strike a nerve with Americans who could possibly then question any necessity of future atomic bombs being developed or used. The USSBS report and the Universal newsreel prove that a carefully orchestrated attempt by U.S. military and government officials existed that successfully controlled the public's ability to imagine the realistic effects atomic bombs produce on a human beings.

On August 31st, 1946, journalist John Hersey's chronicle of his experiences in Hiroshima in May of 1946 were published in the article “A Reporter at large: Hiroshima” in the New Yorker. His descriptive and lengthy story took up the entire issue of the magazine and it contained the first detailed personal accounts of six different Japanese citizens that he interviewed who survived the Hiroshima blast. Hersey's article informed in shocking detail that the power of the bomb was so humungous that some people were completely vaporized into thin air while others eyeballs were completely melted out of their eye sockets. The article (which soon was published as a full length book) contained no photographs that would definitely have caused readers to have a more vivid mental image to what they were reading. Unfortunately, the only photographs shown in the issue were advertisements.11

In the summer of 1952, the publishing ban on film and photographs was lifted in Japan by U.S. occupational forces. At last, close to seven years after what occurred, photographs taken in the immediate aftermath of the nuclear blasts at Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be released for public viewing.

In contrast to the large number of landscape photographs previously released, some of the greatest detailed photographs showing the dramatic suffering and death of civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were released. Japanese photojournalist Eiichi Matsumoto was one of the first photographers on the scene and his photographs were confiscated by U.S. military personal in 1945. However, Matsumoto and his partner Hajime Miyatake ended up disobeying local occupational authorizes and both secretly keep negatives for themselves. Matsumoto only took a small number of pictures with humans because he became too overwhelmed at what he was witnessing and wanted to spare those killed or wounded the indignity of being photographed.12 After the ban on photographs was lifted, Matsumoto and Miyatake provided their personal photographs to the Japanese magazine Asahi Graph who on exactly the seventh anniversary of when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, published their photographs allowing more people to see the horrifying human effects the atomic bomb on human beings.

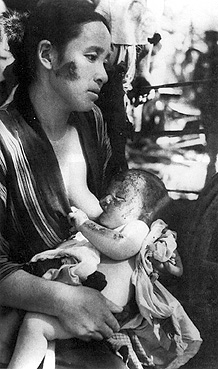

One specific photograph that Matsumoto took allows a viewer to imagine something that O'Donnell's photograph or a mushroom cloud photographs could not accomplish. In Matsumoto's photograph, emotional reactions such as astonishment and fright would surely be felt by many viewers as their imaginations would be immediately opened due to what was depicted in photograph (fig 4).

Fig. 4: A shadow was

all that remained of this individual vaporized by the atomic blast.

While indeed no human suffering was shown in the black and white photograph, a haunting ghost-like shadow of a human next to a ladder stands out in center of the photograph. The photograph demonstrates the unimaginable force the atomic bombs had as those closest to ground-zero of the blast as some of those killed were completely vaporized into thin air with the only evidence of their earthy existence being a shadow left on a wall from where they stood before the bombs detonated. The shadow image provides viewers with a glimpse of what could occur if a nuclear bomb were to detonate over their city during the rising tensions of the Cold War years. The photograph shown for the first time in the Asahi Graph, but never shown to an American Audience, showed viewers how a human being could be killed another human being in such a horrific fashion that they would be vaporized into thin air.

Compared to aerial photographs of the mushroom cloud or buildings that lie in rubble, Matsumoto's photograph allows viewers to put themselves in the place of the departed vaporized victim. Essentially, they could fit their own body into the shadow image, imagine they are ready to climb the nearby ladder, and then after a large flash be completely incinerated. The shadow figure resembles the censorship that occurred after the war. With the picture showing only a shadow, the similarities to aerial footage are striking. For instance, both do not show the victim and the missing image of any human suffering does not exist. Like the O'Donnell photograph previously analyzed, a human element (however minute) allows people to release on a more personal level to what they are viewing.

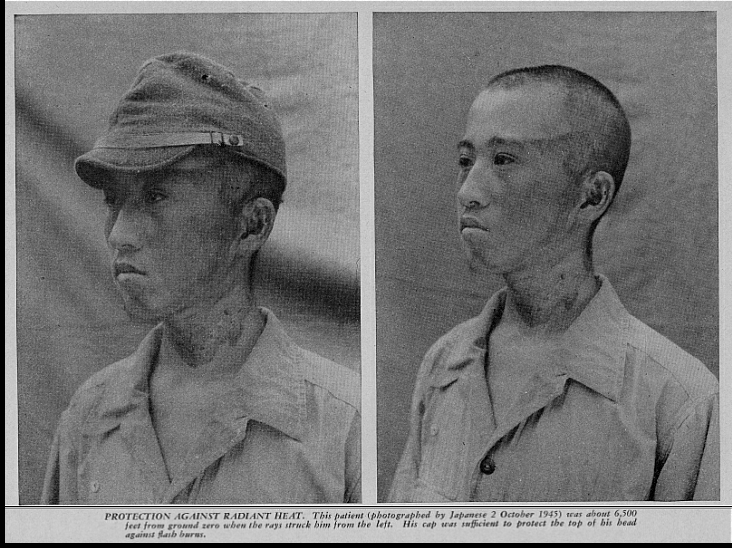

In the US, on September 29th, 1952, Life also published some of Matsumoto's photographs as well as those taken by Japanese photographer Yoshuke Yamahata (the aforementioned shadow image was not included). The issue contained far more detailed photographs of the outcome of the atomic bombings.13 One photograph in particular demonstrates the level of trauma, suffering, and sadness experienced by many Japanese civilians. Taken by Yamahata in Nagasaki shortly after the atomic bomb detonated, the photograph shows a mother, seated in a common Madonna pose, holding an infant covered in burns while the presumed mother gazes off into the distance as she nurses her infant child (fig. 5).

Fig. 5: A mother

nurses an infant after suffering their wounds.

The above photograph produces sympathetic reactions as the mother gazing forward in a cold blank stare punctures the souls of viewers and allow them to immediately relate to the suffering, sorrow, and pain presented.

Professor of sociology Hiro Saito states in his article Reiterated Commemoration: Hiroshima as National Trauma, "after the the publication of the photographs, Japanese audiences (like American audiences) came to know more concretely what they should remember about the atomic bombings: shockingly devastated human bodies against a background of the scorched wasteland."14 Rather than being exposed to the plethora of dull landscape photographs, pictures that showed the human effects the nuclear blasts had on people indeed produced an altered and dramatically different reaction in viewers. The sorrowful gaze on the mother's face and the grotesque burns on an innocent newborn infant provide a great representation of how individual memories of an historic event change as new photographs are released to a mass audience.

Other types of photographs released throughout 1952 and gradually throughout the twentieth century showed more gruesome and detailed photographs of deceased or surviving victims with radiation burns and tumors on their bodies. Those who view such photographs may find them to be too disturbing. But, they open imaginations of viewers much more in comparison to photographs of crumbled buildings.

Regardless of how sensitive one may be toward viewing graphic photographs, they do tell the most realistic story of what happened to those who were under the mushroom cloud in the immediate aftermath of the blasts. However, due to the seven-year span between the historic event and the release of such photographs, recollections of the historic event are slowly erased from memory. Had photographs showing human suffering been released sooner, attitudes and reactions to help victims in Hiroshima and/or Nagasaki would have allowed people to obtain a greater respect for victims much like soldiers who make sacrifices in wartime.

As historian Greg Mitchell writes in his book, Atomic Cover-up: Two U.S. Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki and the Greatest Movie Never Made, “as time passes, new events fill headlines across newspapers and new stories take priority over old stories.”15 The result, public interest in an event wanes to the point that when secret photographs are unclassified a majority of people are oblivious to the fact that photographs actually existed and continue to exist.

In Mitchell's book, he analyzes the reactions people may have when viewing photographs of human suffering the bombs had on those within the blast radius. While the photographs were rarely scene by the public, the photographers themselves often stored their negatives away because they reminded them too much of the harrowing events they previously witnessed. Mitchell provides examples in his book which contains two detailed chapters of interviews he conducted with military photographs and filmmakers Herb Sussan and Daniel A. McGovern who were also amongst the first dispatched to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. While assigned to photograph the rubble of the torched buildings, they decided (like those mentioned in the previously pages) to defy their specific orders and focus more on photographing Japanese casualties residing in medical facilitates. Sussan and McGovern, so shocked by their experience, also concealed a number of photographs and kept in their possession upon returning stateside.16

One vivid and unforgettable experience, recalled by Sussan, is when he came across a severely burned victim being treated in at a make-shift medical facility in Nagasaki. Those documenting at the scene, along with himself, continually filmed and photographed the barely-surviving victim primarily for scientific, objective, and cataloging purposes.

Sussan soon discovered the man's name was Sumiteru Taniguchi. His story is one of the ultimate levels of survival and power that showcases the will of the human spirit. Mitchell writes that Sussan found out years after his tour ended that Taniguchi was forced to lay flat on his stomach for over eighteen months while his scarred, burnt, and maggot-infested body was treated by medical personal while flies continually feasted with delight on his rotting flesh.

Sussan and Mitchell both explain that they developed a deep sympathy for Taniguchi's struggle. While interviewing Sussan, they decided to pick one photograph out of those kept in his personal collection which evoked in them the most profound emotional reaction. Upon coming across the photograph of Taniguchi, Sussan recalled his experience at the time of witnessing his agony. While Mitchell and Sussan compared a photograph of a destroyed building alongside Taniguchi's, they labeled the two photographs respectively “What we saw...what we didn't see..(then, in all capital letters) WHY THE BOMB DIDN'T HIT HOME.”17 The exact photograph Sussan and Mitchell viewed is unknown. However, coincidentally, Taniguchi was also photographed by O'Donnell (see below) (fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Taniguchi's

severely burnt back.

Mitchell writes that the photograph he viewed of Taniguchi “symbolized for me both the atomic bombing and the atomic cover-up.”18 Decades after his first interview with Mitchell, Sussan eventually traveled back to Japan to meet up with Taniguchi (who in the decades after his remarkable recovery dedicated much of his life to publicly advocating for nuclear disarmament). Sussan's reaction to viewing the photograph of Taniguchi decades after he took it provide a prime example of the power of photographs to incite action to aide and comfort those physically and emotionally torn and tattered from their harrowing experience.

In the 2007 HBO documentary White Light / Black Rain, the survival stories and graphic scars still on the bodies of several hibakusha (surviving victims of the atomic bombings) were told. The documentary included an interview with Taniguchi who after slowly removing his shirt showed viewers the gruesome scars (including one of his ribcage protruding from his chest) that still remains and requires constant medical attention even sixty-two years after suffering his injuries.19 At long last, over two decades after Taniguchi's injuries occurred, the American public was able to see in high-definition detail the painful and everlasting difficultly hibakusha have lived with.

If photographs showing the human effect of the atomic blasts were released earlier than 1952, they would have easily opened the minds of people to the amazement and testimony to the will to survive regardless of nationality. Hein and Selden express this missed opportunity when they write,

The individual stories of hibakusha are too powerful and too complex to be denied. They command attention...in their humanity and their pain they reach beyond narratives of necessity and high politics. Each story is so personal...each is such a private hell within the general one. The stories of pain, of tragedy, but also of small kindnesses by strangers.20

In the October 20th, 1956, issue of Life, eight different letters to the editor showed readers' reactions to the photographs published three weeks earlier. The letters all convey emotional reactions of shock and sadness. For example, one letter to the editor sent in by Ben N. Fuson stated,

Sirs: The heartsickness Americans must have felt on seeing the Hiroshima A-Bomb pictures was fully shared by us. But in some slight measure we are making atonement. For we are the proud 'moral parents' of Mitsuko Yoshikawa, A-bomb orphan, whom you see here.

Displayed underneath the text, is a picture of a young girl shown smiling and sitting happily in pile of leaves while she poses for the camera. The article further states that Fuson and his wife have been sending thirty dollars once a year to the Hiroshima Peace Associates foundation. The letter concludes, “We cannot undo Hiroshima, but we can help to mitigate its aftermath.”21

The powerful photographs, such as those displayed in Life in September of 1952, have the power to create a conscionable awareness to provide aid and relief for those depicted. Creating awareness by using sensational photographs dates as far back as the nineteenth-century. For example, when Jacob Riis' book How the Other Half Lives was first published in 1889, the photographs opened people's imaginations and created awareness to the suffering and dreadful living conditions that a large number of immigrants were dealing with in the tenement population of New York. Once people viewed Riis' photographs, the public awareness in correcting the poverty portrayed resulted in a growth of movements to fix the plight of the poor.22 Images of human suffering often create in viewers an awareness to correct whatever is causing others to suffer. Riis' photographs demonstrate that when graphic photographs are published, audiences consequently are able to react and consider various different options one may take to help alleviate the misfortunes others are experiencing. However, the censorship of the atomic-bomb photographs that lasted seven years after the end of WWII prohibited of public awareness from immediately being created which would arouse reconsideration in many towards future development and/or usage of an atomic bomb.

In regards to the Cold War increased governmental funding which resulted in military construction of thousands of additional atomic bombs. Erik Barnouw, historian of radio and television broadcasting, states that the defense industry prospered from keeping film and photographic material showing human suffering secret. Barnouw states,

Mitchell informs of how the lasting impact of the censorship created a ripple effect of which the repercussions last to the present day. The result, the collective memory of the population never truly understood the effect nuclear weapons have on modern society. He writes, that when detailed movies are released to the public, such as the film Original Child Bomb that debuted at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2004, people were easier able to further understand why film and photographs showing human suffering were censored for so long. On why the authorities felt they had to suppress film and photographs, he states that the effect the footage would have had if widely aired earlier would have created a public with a conscious desire for the continued peace during the nuclear age. Such a peace, as argued by Bernouw, would have generated a much lesser amount of tax-payer money being delegated to funding the military.

In the Bulletin of Atomic Sciences article “Hiroshima and the Power of Pictures,” historian and anthropologist Hugh Gusterson explains the long-lasting repercussions that last to this day. He argues that photographs showing the physical effects of nuclear weapons after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki deformed public debates in the years after World War II. Gusterson writes that the censorship of the nuclear weapons photographs relates to photographs censored during the war in Iraq. He writes that “pictures give us something to talk about. That's what pictures do. They evoke feelings. They convey information. They provoke different responses. They incite conversations. And they allow us to feel as if we were there."24 The public outcry that could result from viewing the photograph was therefore minimized to prevent public discourse of whether additional atomic bombs may be used during wartime and whether the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were even necessary.

In Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography by Roland Barthes, he writes that censorship of such images from the masses is “to temper the madness which keeps threatening to explode in the face of whoever looks at it.”25 As a result, viewers could not obtain any realistic mental images which would allow themselves to actually imagine being the scene of the blasts. Americans were unable to make a well informed decision regarding any future funding, testing, and usage of atomic bombs. As stated by Sussan, while he never questioned the necessity to use the atomic bombs, but he grew increasingly frustrated when his desire for his photographs to be seen by a mass audience never occurred to advocate against the future usage of atomic weapons. He writes,

I felt that one, the American people should fully understand the effects of the bomb, since pretty much all they'd seen from Japan was shots of rubble. And, two, if they saw the effects, there would be a groundswell against using nuclear weapons again.26

Like Sussan, other photojournalists in the post-atomic cities developed a great deal of frustration when their personal accounts went unpublished or ignored. George Weller was one of the first journalists into Nagasaki following the atomic bombs being dropped. He disguised himself as a military commander and completed many reports that were published in a book by his son Anthony Weller in 2006. In 1945, Weller, wrote over 25,000 dispatches about what he witnessed in medical facilitates where victims were fighting in vain to survive their injuries. His efforts to have his account of what he witnessed at the time were all futile as General MacArthur (the final decision maker of what types of stories got released to the public) denied all his requests for his accounts to be released back in the U.S.

Weller, in a 1990 radio interview conducted by Swedish journalist Bertil Wedind his life-long frustrations with the general when he said,

MacArthur

didn't want anybody to go there because this would lead to a lot of

compassionate stories about what had happened to the people. I wanted

to get these stories....I had a strong sense that everything written

about this bomb had been wrong.”27

When the extremely vivid descriptions of the effects of the atomic bombs shortly after the blast were detonated, adding the graphic photographs alongside the descriptions would have again aided in public awareness being created against the further development or usage of atomic weapons.

After all, an educated public is indeed somewhat of a threat to those in positions of power as awareness of possible abuses of their power consecutively jeopardizes any possible future utilization such power. Photographs of post-atomic Hiroshima and Nagasaki never contained any information which would threaten national security. Instead, the primary purpose of the censorship imposed was primarily to keep American's patriotism high and prevent the population from being able to developing a caring, understanding, and humanistic approach towards those residing in other nations around the world.

In the book, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War, historian John W. Dower brilliantly describes how racial stereotypes of the Japanese changed after WWII. During the war, American war-time propaganda stereotyped the Japanese as being barbaric simians who were an inherently inferior race. After the war, the stereotypes Americans had of the Japanese began to change as occupied forces, in a short period of time, displayed remarkable mercy, generosity, and goodwill to their former foes. The photographic censorship further prohibited additional Americans from more hastily being able to dispel the stereotype and myth that the Japanese were a fundamentally and scientifically-proven unequal race.28

Suppression of graphic photographs continued on indefinitely after 1952 even though the publishing ban had been was lifted. The primary reason for continued media suppression of the photographs continued with government and media outlets taking a “hands off” approach to publishing questionable photographs as questioning the usage could create a negative stigma on a media outlet of being unpatriotic in the face of a menacing communist threat.

What media outlets fail to recognize is that they actually benefit financially from publishing controversial material to a mass audience. For example, on the seventh anniversary of the atomic attacks, the Asahi Graph was the first to published the atomic bomb aftermath images showing the graphic human effects that resulted from the blasts. A whopping 520,000 copies sold in the first day and 700,000 were sold in total.29 A correlation can therefore be drawn that as the public benefits from gaining awareness about an important issue so too does the media outlet that distributes such information as private profit and attention is gained.

Regulated footage of soldiers, civilians, and/or enemy combatants killed or wounded allows the American public to perceive events at a safe distance from where any military skirmishes may occurs. The result, the American public to easily continue on with their lives being oblivious that anything of a questionable nature has occurred or continues to occur by leaders who orchestrate events without ever fearing that any consequences or public controversy could result which would threaten their position of power.

Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, and especially after recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, it is widely known that the national debt is now reaching epic proportions. With footage showing death and destruction rarely shown to the public, corporations who financially benefit from additional military and government spending prosper as continual amounts of money are invested in national defense. The figurative puppet-masters who decide what the public is allowed to see and not see hold many American imaginations in a continual state of obliviousness while the military industrial complex continually prospers.

A great example of how media restrictions in the twenty-first century effect the collective consciousness of the American mind is stated in an article by Marita Sturken titled “Comfort, Irony, and Trivialization: The Mediation of Torture.” In the 2004 Iraq War, photographs showing torture of enemy combatants at the Abu Ghraib detention facility were leaked to the public. The short-lived public outcry citizens had to the photographs relates to how citizens may have reacted if they were exposed to photographs showing the human effects the atomic bombs had on individuals in Hiroshima and/or Nagasaki earlier than 1952. Sturken argues that prior to the Abu Ghraib photographs being released to the public, Americans had been easily able to distance themselves and as global events played out in an entertaining fashion of which few had concern because they were safe and comfortable being obliviously to any mass atrocities occurring in their name. Sturken writes “Comfort culture is a mechanism of distancing. That is, it functions primarily to create experiences of proximity while offering comfortable modes of distancing.”30

Additional hardship from the censorship physically effected hibakusha as they were prevented from receiving more aid to help them recover from their burns and radiation wounds. Medical knowledge of radiation injuries in the late 1940s and 1950s was in it's infancy. If public awareness to the survivor's plight occurred earlier, further funding and research could have been conducted and an opportunity was missed to discover more satisfactory radiation treatments.

Repercussions of the censorship of atomic bomb victim photographs lasted late into the twentieth century. In 1995, an exhibit at the Smithsonian was planned to commemorate the victims of the atomic bombs. Controversy subsequently erupted and surviving hibakusha were denied the commemoration they deserved. Instead they were and continue to carry a stigma of being collateral damage that unfortunately was necessary to end WWII. Eventually, all that was displayed at the Smithsonian was the airplane the Enola Gay.

Hein and Selden state that honoring the victims, instead of the instrument which brought forth the destruction from the sky, undermines the ability for Americans to be patriotic and remember WWII as a glorious moral war that resulted in victory. They state,

Much of the bomb's specific cultural resonance is with national narratives of the war that define patriotism, power, and honor...In the US, the most sensitive aspect of the 1995 atomic debate centered on implications that Americans were other than kind, generous, decent, and honorable in all aspects of the war. The conflict over the Enola Gay exhibit at the Smithsonian was touched off when critics denounced the exhibit planners for undermining these premises. The Pacific War, culminating in the atomic bombings, has most often been remembered as a victory for American civilization over Japanese barbarism, unlike the political battle against European fascists.31

By referring to the Japanese as being a barbaric people, it is an insult to the still surviving victims of the atomic bombs and that animosity perhaps still remains against America's former foe. If additional photographs had been released and available to a public audience sooner, Americans would have seen the reality and the unimaginable tales of survival the hibakusha experienced. They would then, perhaps, no longer be viewed as a grim reminder of the horrors of WWII that so many wish to forget and bury.

Hibakusha deserve the utmost commemoration, honor, respect, and publicity for having survived the greatest explosions that ever occurred in August of 1945. Truly, they are all brave souls who's sacrifices ended the deadliest war in world history. Their everlasting scars serve as a reminder to us all of the destructive power of the atomic bomb and the necessity that nuclear war must be prevented from ever happening again.

The iconic image of a mushroom cloud menacingly towering towards the heavens to this day surely remains the prevalent mental image one recalls when the atomic bombs were unleashed upon Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The photographs that were never released to the public have led to far too many imaginations being unable to imagine what actually occurred or continues to happen during wartime. Consequently, those hibakusha who survived the nuclear blasts continue to have their stories seldom told. Much like those who perished, the survivors continue to remain...apparitions in the shadow of a mushroom cloud.

1 Greg

Mitchell, Atomic Cover-up: Two U.S. Soldiers, Hiroshima &

Nagasaki and the Greatest Movie Never Made

(New York: Sinclair Books, 2012), 9.

2 “The

War's Ending: Atomic Bombs Obliterate Hiroshima and Nagasaki,”

Life, 20 August 1945, 25-31.

3 U.S.

Joint War Plans Committee, Details of the Campaign Against Japan:

Plans and Operations Division, 1945 (Washington, D.C.: JWPC,

1945), 7.

4 “What

Ended the War: The Atomic Bomb according to Jap Premier, Threatened

the Extinction of the Japanese People,” Life, 17 September

1945, 37.

5 Joe

O'Donnell, Japan 1945: A U.S. Marines Photographs from Ground Zero

(Nashville: University Press, 2005), xiii-xiv.

6 O'Donnell,

54.

7 Laura

Hein and Marc Selden, “Fifty Years after the Bomb: Commemoration,

Censorship and Conflict," Economic and Political Weekly

32 (1997): 2010-2014.

8 U.S.

Strategic Bombing Survey, The Effects of the Atomic Bombs on

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, 1946 (Washington, D.C.: Truman Papers,

1946), 1-56.

9 Erin

Barnett, Philomena Mariani, ed., Hiroshima: Ground Zero 1945

(New York: International Center of Photography, 2001), 5.

10 Jap

Films of Hiroshima, prod. U.S. Army and Navy, 7 min. 13 sec.,

Universal, 1946, newsreel. (multiple representations of the video

are available for viewing on youtube.com).

11 John

Hersey "A Reporter at Large: Hiroshima," New Yorker,

31 May 1946, 15-68.

12 “First

Expose of A-Bomb Damage,” Asahi Graph, 6 August 1952, 1-26.

13 “When

Atom Bomb Struck: Uncensored,” Life, 29 September 1952,

19-25.

14 Hiro

Saito, “Reiterated Commemoration: Hiroshima as National Trauma,”

Sociological Theory 24, no. 4 (2006): 353-376.

15 Mitchell,

43.

16 Mitchell,

24.

17 Mitchell,

62-63.

18 Mitchell,

74.

19 White

Light / Black Rain: The Destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, prod.

and dir. Steven Okazaki, 1 hr. 26 min., HBO Documentary Films, 2007,

DVD.

20 Hein,

Selden, 2014.

21 “Letters

to the Editor” Life, 20 October 1956, 7.

22 Jacob

A. Riis, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of

New York, ed. David Leviatin (Boston: St. Martin's, 2011).

23 Mitchell,

54-55.

24 Hugh

Gusterson, “Hiroshima and the Power of Pictures,” Bulletin of

Atomic Scientists, 5 August 2009,

(http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/hugh-gusterson/hiroshima-and-the-power-of-pictures).

25 Roland

Barthes, The Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography,

trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 117.

26 Mitchell,

55.

27 George

Weller, First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches

on Post-Atomic Japan and it's Prisoners of War,

(New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006): 309-310.

28 John

W. Dower, War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War

(New York: Pantheon Books, 1986), 13.

29 Saito,

365.

30 Marita

Sturken, "Comfort, Irony, and Trivialization: The Mediation of

Torture," International Journal of Cultural Studies 14

(2011): 424.

31 Hein,

Selden, 2011.

Bibliography:

Barnett,

Erin and Mariani, Philomena, ed. Hiroshima:

Ground Zero 1945. New

York: International Center of Photography, 2011.

Barthes, Roland.

The Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by

Richard Howard. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Dower, John W. War

Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War. New York:

Pantheon Books, 1986.

"First

Expose of A-bomb Damage." Asahi

Graph, 6 August 1952,

1-26.

Gusterson, Hugh.

“Hiroshima and the Power of Pictures.” Bulletin of Atomic

Scientists, August 5th, 2009,

http://www.thebulletin.org/web-edition/columnists/hugh-gusterson/hiroshima-

and-the-power-of-pictures.

Hein, Laura and

Selden, Marc. "Fifty Years after the Bomb: Commemoration,

Censorship and Conflict." Economic and Political Weekly

32, no. 32 (1997): 2010-2014.

Hersey, John. “A

Reporter at Large: Hiroshima.” New Yorker, 31 May 1946,

15-68.

Jap Films of

Hiroshima. Produced by United States Army and Navy. 7 min. 13

sec. Universal, 8 August 1946. Newsreel.

Jenkins, Rupert,

ed. Nagasaki Journey: The Photographs of Yosuke Yamahata August

10, 1945. San

Francisco, C.A.: Pomegranate Artbooks, 1995.

“Letters to the

Editors: Atomic Bomb Pictures.” Life, 20 October 1952, 7.

Mitchell,

Greg. Atomic Cover-up:

Two U.S. Soldiers, Hiroshima & Nagasaki and the Greatest Movie

Never Made. New York:

Sinclair Books, 2012.

O'Donnell, Joe.

Japan 1945: A U.S. Marine's Photographs from Ground Zero.

Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005.

Riis, Jacob. How

the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York.

Edited by David Leviatin. 2d ed. Boston: Bedford / St. Martin's,

2011.

Saito, Hiro.

"Reiterated Commemoration: Hiroshima as National Trauma."

Sociological Theory 24, no. 4 (2006): 353-376.

Sturken,

Marita. "Comfort, Irony, and Trivialization: The Mediation of

Torture." International

Journal

of Cultural Studies

14 (2011): 423-440.

U.S. Joint War

Plans Committee. Details of the Campaign Against Japan: Plans and

Operations Division,

1945. Washington, D.C.: JWPC, 15 June 1945.

U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, The

Effects of the Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,

1946. Washington, D.C.: Truman Papers, 30 June 1946.

“The War's

Ending: Atom Bombs Obliterate Hiroshima and Nagasaki.” Life,

20 August 1945, 25-31.

Weller, George.

First Into Nagasaki: The Censored Eyewitness Dispatches on

Post-Atomic Japan and

it's Prisoners of War. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2006.

"When

Atom Bomb Struck: Uncensored." Life,

29 September 1952, 19-25.

“What

Ended the War: The Atomic Bomb, according to Jap Premier, Threatened

the Extinction of the Japanese People.” Life,

17 September 1945.

White

Light / Black Rain: The Destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Produced and directed by Steven Okazaki. 1 hr. 26 min. HBO

Documentary Films, 2007. DVD.